By Dana M. Grimes, Esq.

DNA Evidence

In the past few years, advancements in PCR-based DNA testing and forensics have caused monumental leaps in the probative value of DNA evidence and the use of DNA testing in criminal investigations. DNA evidence is strong and it is valuable, but it is not always available and is not always the end of the story. The Combined DNA index system in the US now contains over 5 million DNA profiles.

DNA is no longer reserved for murder or rape cases. It is now routine to see DNA tests in many felonies, from assaults to residential burglaries. It is becoming increasingly common in San Diego for criminal defense lawyers to pick up discovery suggesting numbers that sound straight out of Kurt Vonnegut’s imagination, like there is a “one in sextillion” chance that our client was not at the crime scene. The national DNA databases are solving hundreds of crimes per month with “cold hits,” and DNA evidence has exonerated many innocent defendants who have served years in prison. (Of course, a number of unlucky prisoners have been exonerated after their executions.) The latest development in this field is familial DNA, which in June of 2010 resulted in the arrest of alleged serial murderer Lonnie Franklin. Franklin was not in the DNA data basis, but his son was. Police looking for a DNA match for murders of a serial killer in LA found that Franklin’s son was close enough that the killer was probably an immediate family member. Upon further investigation, they obtained a DNA sample from Lonnie Franklin, which was a match. This is a huge development in investigation of crime with DNA, greatly expanding the scope of potential suspects beyond present DNA data bases, to include family members of those in the data bases.

Trace Evidence

Once a main focus of forensic labs, trace evidence has been somewhat neglected with the tremendous increase in the use of DNA evidence. Hair comparison and fiber comparison is becoming a lost art. In hair comparison, hairs are collected and used to obtain DNA samples as the hair root can be a source of DNA.

Shoe and tire impression evidence is still utilized with frequency. (You may recall the bloody shoe prints left at the murder scene at Bundy Drive by a pair of size 12 Bruno Magli’s in the O.J. Simpson case.) Paint identification and comparison can be compelling evidence and is commonly used in hit and run cases involving death or serious injury.

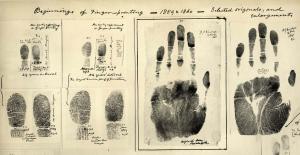

Fingerprints

Prints have taken a back seat to DNA and have been subject to some recent criticism. While comparison of latent prints to the properly rolled legible prints of an individual known or suspected of being at a crime scene can be very strong evidence, the FBI created grounds for cross-examination of fingerprint experts in 2004 when they arrested an Oregon lawyer and former Army lieutenant and jailed him for two weeks. An FBI “super computer” and FBI fingerprint examiners positively identified the lawyer as having left a partial print on a bag of detonators linked to terrorists who bombed trains in Madrid resulting in about 2,000 injuries and 191 deaths.

The FBI made the arrest even though the latent print examiners for the Spanish National Police notified them three weeks prior to the lawyer’s arrest that they had concluded that the print did not belong to him. (Prior to his arrest, FBI agents entered the attorney’s home without his knowledge under the authority of the Patriot Act, arousing the family’s suspicion of bolting the wrong lock on their way out and by leaving trace evidence – a shoe impression on a rug that did not match any family member’s shoes. Subsequently, in an FBI raid, agents took the attorney’s computers, modem, safe deposit key and papers including what they termed “Spanish documents” – which later apparently turned out to be the Spanish homework of one of the attorney’s children.) The federal government ended up settling the civil claim of the lawyer, his wife and three children for close to $2 million.

Firearms

Despite its popularity in the film industry, gunshot residue (which is technically in the category of trace evidence) is not one of the strongest areas of forensic science and has been the cause of mistaken testimony and wrongful convictions. Microscopic comparison of fired bullets and expended cartridge casings, on the other hand, is a more reliable science. Striations (scratches) on fired bullets are unique to every firearm, as are the corresponding marks left on expended cartridge casings. Even when the suspected firearm has not been seized, the characteristics of a bullet or casing can still be very important to the case. For example, 6 groove, right-hand twist rifling on a bullet of a specific caliber can sometimes identify the manufacturer of the firearm, or at least eliminate many manufacturers (hopefully eliminating any firearms ever owned by your client). DNA testing of firearms, as well as cartridge casings left at the scene of homicides, sometimes proves very effective in identifying the shooter.

Similarly, microscopic comparison of marks left on the cartridge case by the firing pin, chamber extractor, ejector, or breech face of the firearm can be useful in determining the manufacturer. Some gang members have learned this and have taken to using revolvers instead of semi-automatics to avoid leaving the cartridge casings, but many gangsters continue to fire away with semi-automatics. When police criminalists find shell casings at shooting scenes, in addition to examining the casings to determine the weapon which was used, examination for traces of DNA can sometimes identify the person who loaded the cartridges into the firearm.

Some hispanic gangs have recently shown a preference to stab their rivals, or to shoot them at close range after walking up to them. It is said that this is a result of a decree from members of hispanic prison gangs, in response to a drive-by shooting which resulted in the accidental death of a young girl who was an innocent bystander of the shooting. This civic-minded concern for collateral damage has not yet been seen among other ethnic groups.

Blood Spatter

Homicides are not the only cases involving large amounts of blood spatter evidence; we see it in incidents involving knives, broken bottles and even fist fights. The re-creation of an incident from blood spatter is not nearly as precise as some of the above types of forensic evidence, but it can be useful. A good blood spatter expert – the good ones readily acknowledge the lack of scientific certainty in this analysis – can examine the crime scene photographs and the blood stained clothing and help you understand the probability of how many blows were struck, whether it was with the left hand or right hand, what kind of weapon may have been used, the distance of the parties from the blood stained wall or floor, etc.

Evidence Collection

If at all possible, we go to the crime scene, with an expert, right away; but often our expert has to rely on the photos and observations of law enforcement. In one recent case, the homeowners of the crime scene had their blood-stained carpet steam cleaned within hours after the police left. [The DA’s office later sent our client the bill.] In that case, which involved a multi-person melee at a crowded party and serious injuries, no blood samples were collected from any of the many blood spots on the carpet – so there was no way of knowing who bled where.

The San Diego Police Department Forensic Unit has Forensic Specialists who are on call 24 hours a day. They respond to homicides, officer-involved shootings and other priority cases, at the discretion of the detectives on the scene. However, in most serious felony and strike cases, the evidence at the crime scene is collected by patrol officers, who do not always use the precise and scientific approach of the Forensic Specialists.

The CSI Effect

While interesting and at times informative, CSI and the various spin-offs of the hit television show take considerable artistic liberties. Jim Stamm, a private consultant in crime forensic science who recently retired as the supervisor of the San Diego Police Department’s Forensic Science Unit, says that his wife will not let him watch CSI anymore because it makes him too upset.

However, CSI is part of the fabric of our culture, and on any jury you are going to have a number of people who expect the case to be solved by this type of evidence. This can be a problem for DA’s, who often voir dire on this topic. As defense lawyers, we try to present scientific evidence whenever we can, and when the scientific evidence appears to all support the DA’s theory we need to be prepared to address it in cross-examination.

In February 2009, the National Academy of Sciences issued a sweeping critique of the nation’s crime labs. It reported that forensic scientists for law enforcement agencies “sometimes face pressure to sacrifice appropriate methodology for the sake of expediency.” In the recent Melendez-Diaz decision, the Supreme Court held 5-4 that crime laboratory reports may not be used against criminal defendants at trial unless the analysts responsible for creating them give testimony and subject themselves to cross-examination. Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts (2009) 129 S.Ct. 2527.

Cross-examination of witnesses, Justice Scalia wrote, “is designed to weed out not only the fraudulent analyst, but the incompetent one as well.” Id., 129 S.Ct. at 2527. He added that the Confrontation Clause of the Constitution requires allowing defendants to confront witnesses even if “all analysts always possessed the scientific acumen of Mme. Curie and the veracity of Mother Teresa.” Id.

The United States Supreme Court has decided, in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, that the the principals of Melendez-Diaz v. US apply to lab results in DUI cases. It was a denial of defendant’s right to confrontation to allow testimony of the blood analysis by a witness who had neither performed or observed the actual analysis.

UPDATE January 2018- The advances made in recent years in DNA and other crime scene evidence continue to be very valuable. Computer and cell phone forensics is the area in which there has been more action, both in the amount of evidence that can be recovered from these devices, and the developing case law determining under what circumstances law enforcement can access this information.