By Dana M. Grimes, Esq.

The Two Federal Money Laundering Statutes

Classic money laundering cases involve the indictment of accountants, real estate professionals, bankers, and anyone else who helps a criminal organization disguise its earnings. For instance, when suspected members of the Sinaloa drug cartel were caught shopping for AK-47’s in Arizona a few years ago, the defendants charged with acting as straw purchasers for the firearms were indicted on federal money laundering charges as well as firearms charges. (Grand Jury Indicts 34 For Allegedly Buying Guns Destined for Mexico Drug Cartels, The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 26, 2011.)

Classic money laundering cases involve the indictment of accountants, real estate professionals, bankers, and anyone else who helps a criminal organization disguise its earnings. For instance, when suspected members of the Sinaloa drug cartel were caught shopping for AK-47’s in Arizona a few years ago, the defendants charged with acting as straw purchasers for the firearms were indicted on federal money laundering charges as well as firearms charges. (Grand Jury Indicts 34 For Allegedly Buying Guns Destined for Mexico Drug Cartels, The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 26, 2011.)

The primary federal money laundering statutes are Title 18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957, two substantive offenses added to the criminal code by the Money Laundering Control Act, enacted in 1986. The prohibited conduct includes conducting financial transactions involving the “proceeds” of specified unlawful activity, albeit in different ways. Section 1956(a)(1) reads:

Whoever, knowing that the property involved in a financial transaction represents the proceeds of some criminal activity, conducts or attempts to conduct such a financial transaction which in fact involved the proceeds of the specified unlawful activity . . . with the intent to promote the carrying on of the specified unlawful activity . . . [shall be guilty of a crime.].

Section 1957(a), by contrast, reads:

Whoever, in any of the circumstances set forth in subsection (d), knowingly engages in or attempts to engage in a monetary transaction in criminally derived property of a value of greater than $10,000 and is derived from specified unlawful activity . . . shall be [guilty of a crime].

The crimes differ with respect to the knowlege element; Section 1957 “does not require that the defendant know of a design to conceal aspects of the transaction or that anyone have such a design,” whereas Section 1956 does require a knowledge element. See, United States v. Wynn, 61 F.3d 921, 926-27 (D.C. Cir. 1995).

Proceeds of Specified Unlawful Activity

The term “proceeds” has received significant judicial attention recently. Interpreting Justice Scalia’s four-judge plurality opinion in the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Santos, 553 U.S. 507 (2008) is like wrestling an alligator, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has struggled to apply it, along with Justice Stevens’ concurrence.

In Santos, the defendant was convicted of operating an illegal lottery and Section 1956 – money laundering – he challenged his money laundering convictions on the grounds that his transactions were merely the distribution of receipts to gamblers, as opposed to the profits of the illegal lottery. 553 U.S. at pp. 509-10. Justice Scalia agreed, and held that to accept the government’s position would yield an unusual result – everyone who operated an illegal lottery would, by default, be committing the crime of money laundering; Scalia found this created a “merger problem.” Id. at 515-16.

The recent Ninth Circuit decision in U.S. v. Bush, has shed some light on how to identify when the merger problem exists, holding “. . . the import of Santos is its requirement that a court evaluate whether the government has been redundant in its prosecution of a fraudulent scheme – that is, whether the charges separate necessary parts of the whole and treat them as independent bases for criminal activity.” U.S. v. Bush, 2010 DJDAR 18138, citing Santos 553 U.S. at pp. 515-17.

The Broad Scope of Title 18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957

These statutes were originally designed to fight organized criminal organizations, but their application is much broader than that. The “specified unlawful activity” that is covered by the statutes runs the gamut from racketeering – acts or threats involving murder, kidnapping, gambling, arson, robbery, bribery, extortion, dealing in obscene matter – to welfare fraud. Other specified unlawful activity includes bribery, counterfeiting, smuggling, theft from interstate shipments, embezzlement, mail fraud, wire fraud, the manufacture, importation, receiving, concealment, buying, selling, or otherwise dealing in a controlled substance, and much more. (See, Title 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(7).)

Thus, money laundering can be charged in an indictment from which profits were gained from any of those activities. As a regulatory measure designed at preventing money laundering and flagging suspicious transactions, all financial institutions are required to report transactions involving more than $10,000 in cash, and transactions that appear to be structured to avoid that limit (i.e., patterns of $9,000 deposits), or are suspicious in other ways, are investigated. Businesses and professionals, including lawyers, are required to file Form 8300 with the IRS upon receipt of more than $10,000 in cash from a client.

Although the way money laundering is depicted in mafia movies is often sophisticated, sometimes the crime is not particularly organized. Take, for instance, the average urban marijuana cultivator, who has no management skills beyond those required to install lighting and irrigation systems in the bedrooms of rented houses, but who does have a very green thumb. He may find himself cultivating amounts of marijuana that are beyond the most liberal interpretation of California’s Compassionate Use Act (Health & Saf. Code § 11362.5). The fortunate cultivators get caught before their operations become large enough to pique the interest of the federal authorities. Cultivators who end up with large amounts of money will sometimes ask friends or family members to help them disguise the source of the money by helping them buy houses or make other investments. Sometimes a mother, girlfriend, or friend who were otherwise law abiding citizens have fallen afoul of the broad sweep of the federal money laundering statutes by agreeing to assist the cultivator in investing the money. The federal sentencing guidelines for money laundering are driven primarily by the amount of money involved, and can be quite severe.

Leaks from financial institutions have been very helpful in shedding some light on the secret world of high level money laundering. The privacy rules for banks in Switzerland have made those banks instruments of money laundering for generations. In 2008, an HSBC employee named Hervé Falciani downloaded massive amounts of data from HSBC in Switzerland, and gave it to French authorities. Swiss authorities made efforts to have Falciani extradited to Switzerland for prosecution for theft of this information, but French authorities declined. Much of his information was shared with authorities in other countries, resulting in tax evasion and money laundering investigations of many wealthy people

The Panama papers, which disclose the identities of thousands of wealthy investors for whom the law firm Mossack Fonseca had set up shell corporations, has also been a very valuable source of information for authorities investigating money laundering and tax evasion. A lot of work still needs to be done to pass legislation requiring more financial transparency. Many countries, and even some states in the US, such as Delaware and Nevada, allow financial secrecy which is contributed to money laundering and tax evasion

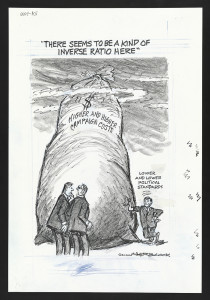

A Sidenote: Political Money Laundering

Political money laundering involves very different activities and different statutes than Title 18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957; the main commonality is the interest of veiling the sources of income from authority. There have been many cases in California where business owners have tried to circumvent limits on political campaign contributions by directing employees to make contributions to political campaigns, and then reimbursing the employees. We have represented people on both sides of these cases – the business executive contributor side and the politician payee side. Most of the lower level violations are resolved by negotiating a fine with the Fair Political Practice Commission (FPPC).

These fines can be substantial. The highest fine ($895,000) and largest number of counts (236), occurred in a case against a Taiwanese shipping company.

The statutes for California political money laundering cases include Government Code §§ 84301, 84302, and 84301(a). Most prosecutions under California law have been for misdemeanors, but there have been exceptions. In addition to filing felony charges under the above Government Code sections, these cases can involve felony charges of Conspiracy (Pen. Code § 182(a)(1)), and Perjury (Pen. Code § 118). Anyone receiving political contributions should research the rules on the FPPC website.

High-End Political Money Laundering

On November 24, 2010, former Republican House Majority Leader Tom “The Hammer” Delay was convicted of money laundering and conspiracy. Prosecutors in Texas proved to the satisfaction of the jury that Delay conspired to use his Texas-based PAC to send $190,000 in corporate money to an arm of the Washington-based Republican National Committee. Delay effectively ran Congress during most of George W. Bush’s presidency, and was instrumental in implementing policies of George W. Bush. Delay’s conviction was overturned on appeal, but there are state and federal prosecutors throughout the country who are prepared to bring similar charges against other politicians if the evidence supports prosecution. However, these cases are now harder to prove. In Skilling v. United States, the US Supreme Court ruled the prosecution must prove a quid pro quo in return for the money. The payment must amount to a bribe or a kickback.

MONEY LAUNDERING BY FOREIGN RULERS- The prosecution of the management of the giant Brazilian construction company, Odebrecht, led to a trial of hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes to public officials in other countries. This has resulted in the convictions of officials at the highest levels of government in countries including Peru, Argentina, Columbia, and Bolivia. As we enter 2018, the rulers of many countries in Africa, Latin America, and Asia steal billions of dollars of public funds and send it to other countries, including the US, often while their own people are starving. The the leak of the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers caused a lot of furor, but the use of corporate shells makes it hard for US prosecutors to find the true owners of many properties. The White Collar Professors’ Blog gave an award for Money Laundering Collar of the Year to Developers in New York and Los Angeles who sell 8 figure condos to shell corporations owned by larcenous foreign leaders.